Philosophy

In general, Philosophy is a study of Knowledge: how it is obtained, epistemology; what it concerns, ontology; and, how it is structured, meta-physics. The Philosophy of Science (Pos) is a particular investigation of Scientific Knowledge. From better undestanding Science some questions maybe answered: what counts as Science (demaraction)?; what makes science successful at producing Knowledge (justification)?; what makes for better Science Knowledge (normativity)?. The goal is not to understand Scientific practice as guide to improving other areas of Knowledge.

Brief History of PoS

Warning

Everything mentioned here is truncated and much more can and has been said - many relevant details have been omitted

- Other views are available

Empiricism

Much of modern (ca. C16+) Philosophy of Science was spent searching for solid epistemic grounds for the success of Science or confidence in Science.

In the Eighteenth century much of this work reduced to identifying an empirical method in Science which could justify its high status as an ontological authority from its unique epistemic privilege.

Summary of Empiricism:

-

Deduction does not do enough: need amplicative inference

-

Inductivism seems relevant but incomplete. Additional principles are required to interpret data and guide inferences. Some reason to think these are not empirical - cf. Riddles of Induction

-

Hypothetico-Deductive method moves empirical aspect to testing. Invention of a theory is separate from justification.

- Emphasis on theory confirmation has problems with how to deal with trivial agreement - cf. Hempel's Paradox

- Emphasis on falsification avoid limitations of agreement between theory and expriement by presenting tests as disposers of poor theories rather than anointers of kings. Falsification is used as a guide for progress and a demarcation principle is possible.

Empiricism seemed a viable justification ... But Wait!

Kuhn

Kuhn avoided further analysis of Science with repect to some ideal activity and instead focussed on the history of Science.

For Kuhn, Science consists Paradigms

- sets of hypotheses used to solve problems: e.g. Copernican solar system, Quantum Mechanics

- these sets include (sub-)theories to make empirical predictions with the required assumptions (stated or implicit) and practices – perhaps undocumented

A Paradigm will have ways of obtaining, arranging, analysing data according to theory and practice

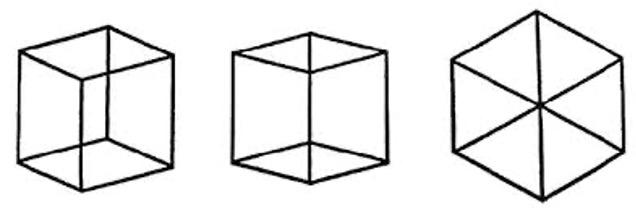

There is no guarantee observations are respected across Paradigms Revolution for Kuhn is a big thing – comparable to gestalt shift

Within a Paradigm anomalies arise when data doesn’t fit the predictions, but these don’t necessarily end (i.e. falsify) the Paradigm.

Several strategies available to keep hypotheses:

- Dismiss test

- change auxiliary hypothese, e.g. how the measuement apparatus is expectedc to work

- change theory, e.g. allow for varying contexts

Kuhn argued history shows:

- too many anomalies inspire new Paradigms - people will go elsewhere

- there is no rule to predict when people change Paradigm

- Scientists will find some way to decide winner between competitors

The way competing Paradigms are assessed is a matter of context

- historical: what is the cognitive environment of the actora

- sociological: what mechanisms are avaiable for people to interact